But How Do We Assess This?" />

But How Do We Assess This?" /> But How Do We Assess This?" />

But How Do We Assess This?" />

We know that creativity is vital for student learning. We also know that we tend to value the things we assess. However, when we assess creativity, we can unwittingly cause students to become risk-averse. So, how do we assess creativity in a way that encourages students to become more creative?

If you enjoy this blog but you’d like to listen to it on the go, just click on the audio below or subscribe via Apple Podcasts (ideal for iOS users) on Stitcher (ideal for Android users), on Amazon Podcasts, or on Spotify.

When I wear my Apple Watch, I pay greater attention to my activity level throughout the day. I find myself standing up to move in order to get that “move” circle closed. I make sure I am standing up at least once an hour. By contrast, when I am not wearing my watch, I tend to sit down more often. The visual cues not only provide data but they also change my behavior. Similarly, for the last 18 months, I have tracked what I eat so I don’t unintentionally fall back on old habits of mindlessly overeating or even choosing junk food as my go-to when I am feeling anxious.

I notice this in other areas of my life. I have progress bars that I use to gauge whether I am on track for various projects. Whether intentional or not, I notice the percentage of likes to dislikes on my YouTube videos. But it’s not just quantitative data. When I am intentional about reflecting on how I am doing as a dad, I am more likely to set boundaries on my time and plan activities we can do together. When my wife and I have a deep conversation about our marriage, we are both more intentional about spending quality time together or writing each other notes or planning date nights (which is admittedly hard during the pandemic). While I wouldn’t tend to think of these conversations or reflections as assessments (indeed, I would cringe at filling out a marriage rubric), at the core, that’s what they are.

So in every facet of life, the areas we assess become the things we value. Similarly, we tend to assess the things we value. If you value money, you’re more likely to check your bank accounts and retirement portfolio. If you value running, you are more likely to track your mileage — which, in turn, keeps you focused on running.

The same phenomenon is true in teaching. We value what we assess and we tend to assess what we value. A school might have a vision statement about developing lifelong learners who fall in love with learning. However, when teachers keep data charts on reading fluency or on benchmark test scores, there is a higher likelihood that teachers will teach to the test. Lifelong learning becomes a lofty goal but the frequent use of standardized tests can shift the focus away from the love of learning and toward higher academic achievement.

When we don’t assess something, we tend to under-emphasize it. Students, in turn, might internalize the message that it’s less important. So, while we may value creativity, if we don’t assess it, we might neglect it. When I began as a self-contained teacher (teaching all subjects), I was far more likely to neglect creative thinking in math and language arts because these were tested subjects and I felt the pressure to have students score well on our district assessments. Creative work became the thing I would get to “when we have time for it.” If I wasn’t careful, I would treat creative work as a dessert rather than the main course. I was cautious about implementing project-based learning until I could see that it led to higher achievement gains. In other words, the school-wide focus on test scores reshaped my teaching.

So, we have this reality that we value what we assess. If we fail to assess something, we are far more likely to neglect it. It would seem, then, that teachers should assess student creativity.

When I first began crafting PBL units, I would create rubrics that included a category for creativity. I wanted students to value creative thinking. I would point out that section on the rubric and talk about the need for creative risk-taking. However, I noticed that certain students became risk-averse. What if their work wasn’t creative enough? What if I gave them a low score? Students would ask for examples of a creative versus a non-creative project. A few teams would pull me aside and ask, “Is this creative enough?” or simply, “Is this what you’re looking for?”

By assessing creativity, I had turned creative thinking into something high-stakes. Rather than focusing on the intrinsic enjoyment of the creative process, students were fixating on the extrinsic score of the rubric. They took fewer creative risks and engaged in less divergent thinking. They were far more likely to copy the exemplars rather than find their own creative voice. In a few cases, this external pressure led to higher performance and better creative thinking. These students wanted to prove how creative they could be. The rubric seemed to light a fire in them. But even then, most of these groups fixated on how I would perceive their creative work.

I was left with these dueling truths. On the one hand, if I didn’t assess something, I would be likely to neglect it. On the other hand, when I gave students a score on the creativity of their project, it actually led to creative risk-aversion. At that point, I began to experiment with different ways of assessing creativity. I eventually realized that the issue isn’t whether or not we should assess creativity so much as the way we assess creativity.

Over time, I began to shift away from having me assess the creative product and toward having students assess their own creative process. Along the way, I made three key paradigm shifts in how I approached assessment and creativity.

When I first added creativity to the project rubric, students grew risk-averse. They were worried that their finished work wouldn’t be “creative enough.” The fixation on the product actually led to a decrease in creative risk-taking. I’ve noticed the same thing in my own life. If I try to make something creative, I end up trying too hard. The end result is either something derivative or something overtly weird. This happens with avante-garde artists who focus too hard on trying to be different rather than trying to make something meaningful. It happens with authors who get stuck in their own head trying to avoid anything cliche who end up creating a novel that doesn’t have any narrative structure at all.

There’s a similar danger when people self-assess how creative they are as people. You end up with people who say, “I’m not really the creative type.” But there’s no such thing as a creative type. We’re all creative. Every one of us. It’s just that we often need a bigger definition of creativity.

Instead of focusing on the creativity of a product or treating creativity as an inherent personal trait, we can re-frame creativity as a process. It’s not a singular process, either. Creativity involves things like:

This is by no means and exhaustive list. At first glance, these might seem like creative thinking skills. And that’s certainly a part of it. But these are also processes that students can master and mindsets they can adopt. Empathy, problem-solving, and creative risk-taking are all specific actions in the creative process.

By focusing on the creative process, we move away from conversations about creative potential and toward the idea of creative momentum. This is the idea that we don’t have a fixed amount of creative potential. It’s not innate or tied to our personalities. Instead, creative thinking is a skill that we can develop over time.

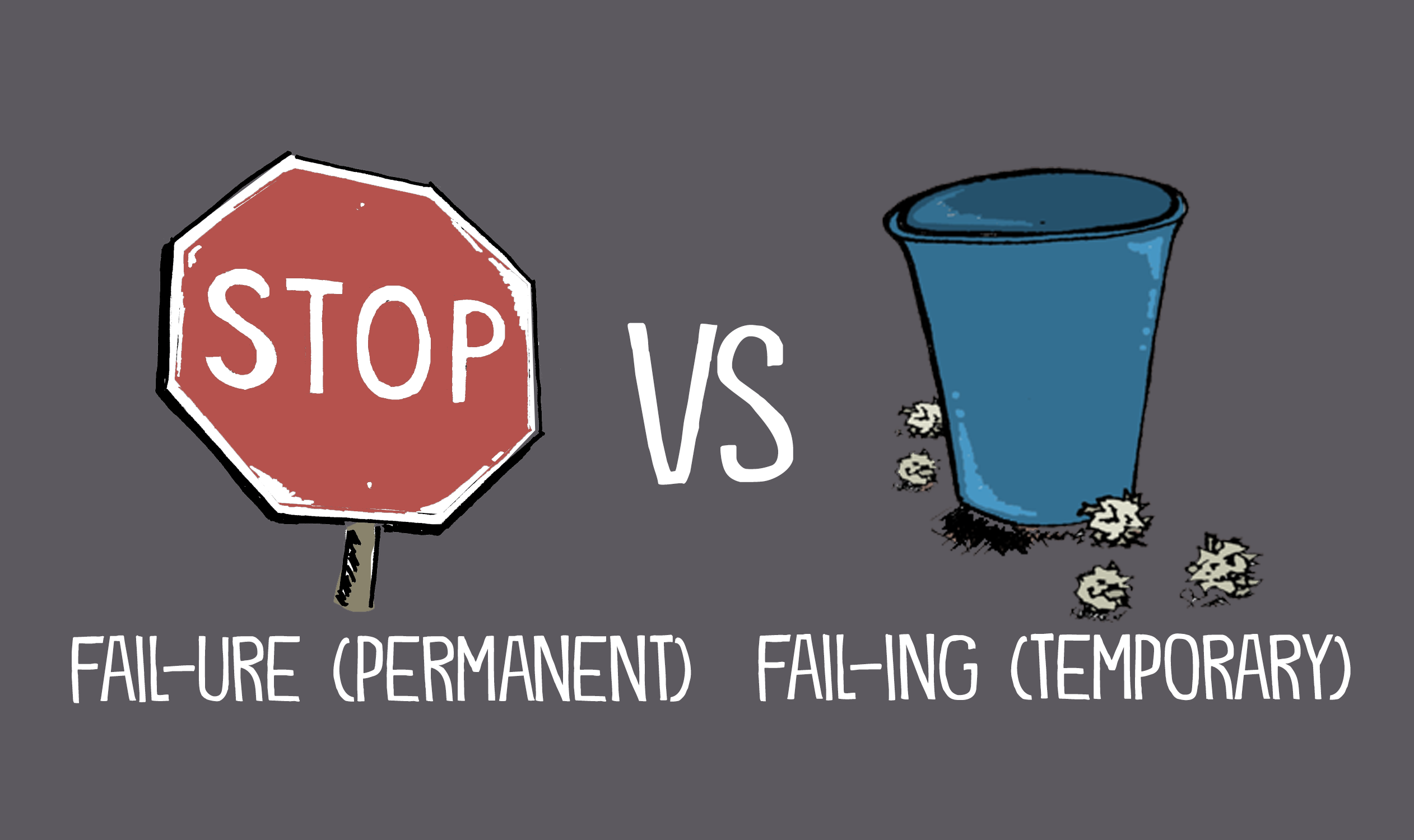

I once worked with a colleague who had students share their “epic fail” at the end of the class period. Students would use the sentence stem, “My epic fail was _____. I learned ______. Tomorrow I will try _______.”

This approach might seem to promote lower academic standards. However, it actually led to better performance and an increase in creative risk-taking. Students internalized the difference between fail-ure and fail-ing.

I walked in one day and watched as this teacher pulled his name out of the cup. He said, “My epic fail was how I taught vocabulary. Students were confused. I learned that I need to simplify the process and make it visible. Tomorrow I will try a TPR approach.” Students stood up and gave him a standing ovation. In this moment, he was modeling humility and creative risk-taking but he was also modeling a growth mindset:

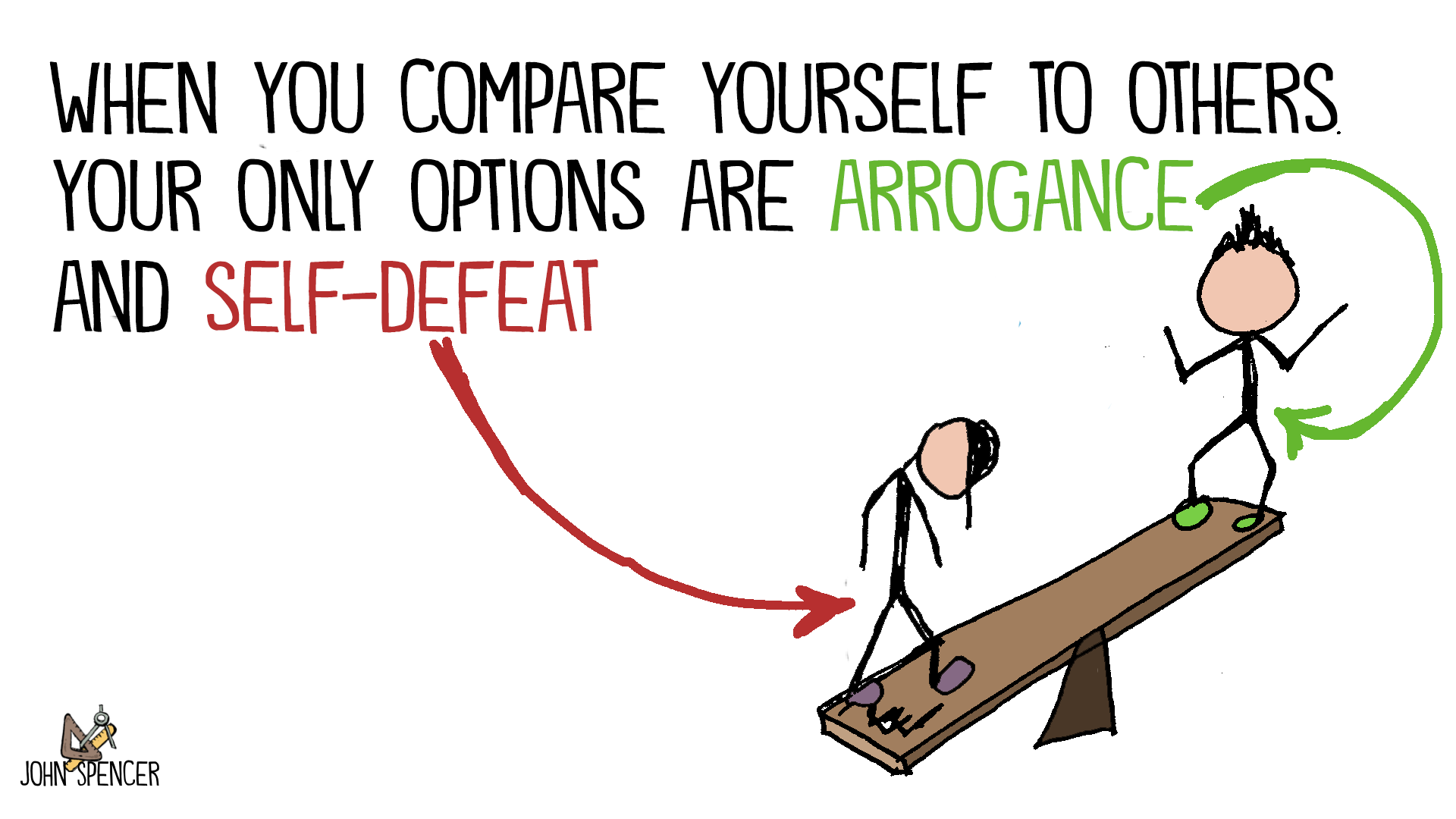

I want students to have a growth mindset around creativity. I don’t want to see students define creativity as an inherent, innate talent. So, as we think about assessing creativity, it’s important that we focus on growth. For this reason, we might want to avoid having students compare their creative process to other students:

Instead, we can ask students to reflect on how they are growing as creative thinkers. This might include a reflection or a self-assessment survey. It might also include comparing their creative work (yes, I realize that this is a focus on the product and not the process) and examine their growth. They might even create portfolios where they share their work but also reflect on their process:

If students are focusing on growth and improvement, they are likely going to do so with a critical eye. So, how do we do this without leading to risk aversion? How do we help students apply a critical lens without falling into self defeat? One way is focus on assessment rather than grading. In other words, teachers can provide feedback on the creative process without assigning a specific grade to the assessment. Students will still value the feedback and focus on their creative process but they can do so without worrying about how it will be graded.

It also helps to ask what assessment strategies promote creative thinking. For example, the fixation on a single right answer in multiple choice tests might harm divergent thinking. However, a concept map might lead to deeper connective thinking and divergent thinking. Allowing students to revise and resubmit work might actually lead to greater creative risk-taking because students will feel the freedom to make mistakes.

When I look back at that failed rubric category, I realize that students were looking externally for an evaluation of their creativity instead of going inward through self-reflection. By focusing on the creative process and using feedback rather than grading, I was able to assess student creativity in a way that still promoted creative risk-taking. However, the biggest shift occurred when students began to engage in self-assessment. In life, most of our key growth occurs through self-assessment and peer assessment. This is why it helps to empower students to own the assessment process.

As we think about creativity, students can own the assessment process by reflecting on their creative thinking, filling out surveys on their creative process, or creating their own portfolios. However, self-assessment doesn’t always need to be self-evaluation. It includes analysis and diagnosis, as students reflect on new ways to solve problems or different ways to engage in a creative work. Here, the assessment focuses less on “better” and more on “different.” We might ask students a question like, “Is there a different way to solve that problem?” or even “How did you approach it this way versus last time?”

In some cases, assessment is descriptive and reflective. When students describe their creative process, it can take some of the judgement an risk-aversion out of the assessment process. Here, they might document their creative process in the form of a video or a podcast where they share what they are doing and what they are learning along the way.